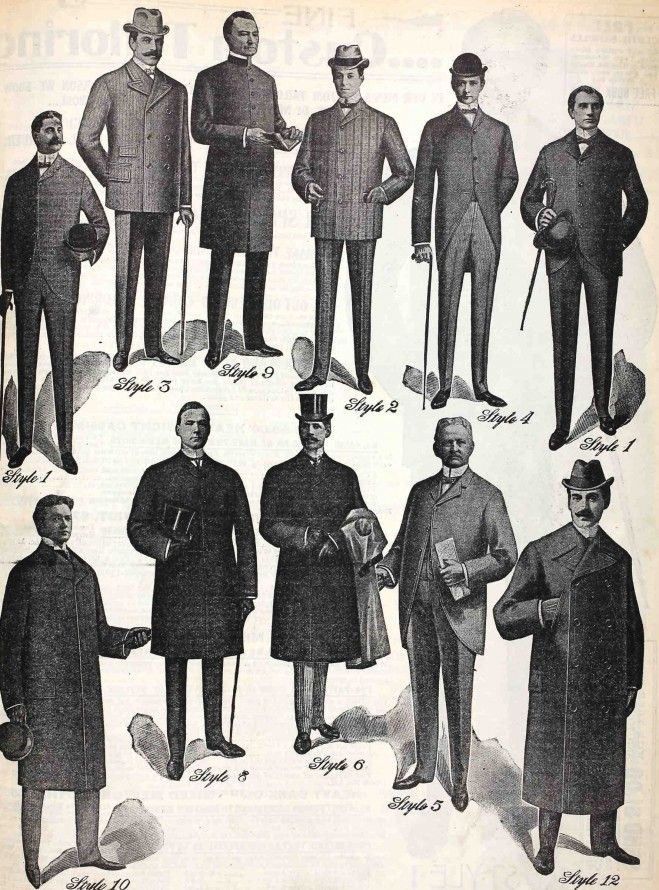

This last week marks the last time in my UCSB graduate student career that I will teach "Music 15", more commonly known as "Music Appreciation". The concept of "Music Appreciation" has a long history that presents particular problems to twenty-first century graduate students and their undergraduate pupils. Around the beginning of the 1900s philharmonic orchestras in Europe and the US began to cater to wider audiences by offering pre-concert lectures aimed at giving unfamiliar listeners—children, lower-class workers, etc.—the active listening skills, musical nomenclature, and conceptual frames necessary for making sense of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, Listz's Les Prèludes, and other "great" works by "great" composers. A good example of these efforts is the New York Philharmonic's Young People's Concerts, lovingly developed in the 20s by conductor/composer "Uncle" Ernest Schelling who used "PowerPoint" presentations done on illuminated glass slides, developed silly mnemonic devices to recognize themes ("This is the symphony that Schubert wrote and never finished..."), and made use of various props. (Interestingly, the early Soviet government initiated a massive Music Appreciation program to involve the proletariat in "high" art, even during the famine and winter of the Civil War following the October Revolution!)

"Uncle" Ernest Schelling (1876-1939) and his well-dressed dog. He seems to have the sense of humor necessary to appeal to an audience of children. I'd love to write a book on this guy and spend some time in the University of Maryland archive collection.

A century later, we still have Music Appreciation, both as part of educational outreach at orchestras, such as the New York Phil, and as undergraduate courses at universities, such as UCSB. I have taught this class (which has a capacity of ~70 in the summer to ~450 per quarter during the school year) seven times as a teaching assistant and six times as the lecturer/associate. In the summer of 2015 I spearheaded the department's effort to revamp the course and I've been fine tuning it ever since in the hopes that it's future will be bright. Here are some of our pedagogical concerns and solutions.

- Music + Culture: Often "Classical" music is touted as a timeless, universal music, which has tends to make it untouchable and unrelatable. It was important to put this music back into a historical and cultural context to show how musical choices had value for those making and consuming it. This approach speaks to me because context is one of the things that excites me about music, it was possible get away from historical teleology by making units based on cultural issues, and it allowed me to get away from canonical pieces and composers (I developed a Music and Childhood unit from sections of my dissertation).

- Four Ways of Listening: It wasn't enough to have students learn to recognize selected "masterpieces" by ear using terminology (eg. melisma, sonata form, pizzicato, Klangfarbenmelodie) that they could barely define, not to mention use in a cogent sentence. Not to say that critical listening isn't important, but it should be taught in a more holistic way, which I divided into:

- Technical/Intuitive Listening: The use of any technical language a student may have from exposure to music—there's always one kid who raises their hand and starts talking about cadential hemiolas!—but also encouraging students to make attempts to put words to what they hear the music doing in an intuitive sense—getting louder, speeding up, building in energy, getting confusing, playing a singable tune. All of those observations are an attempt to interact with the development in the music and it's vital to encourage the innate human ability to notice sonic changes. Specialized language can come later.

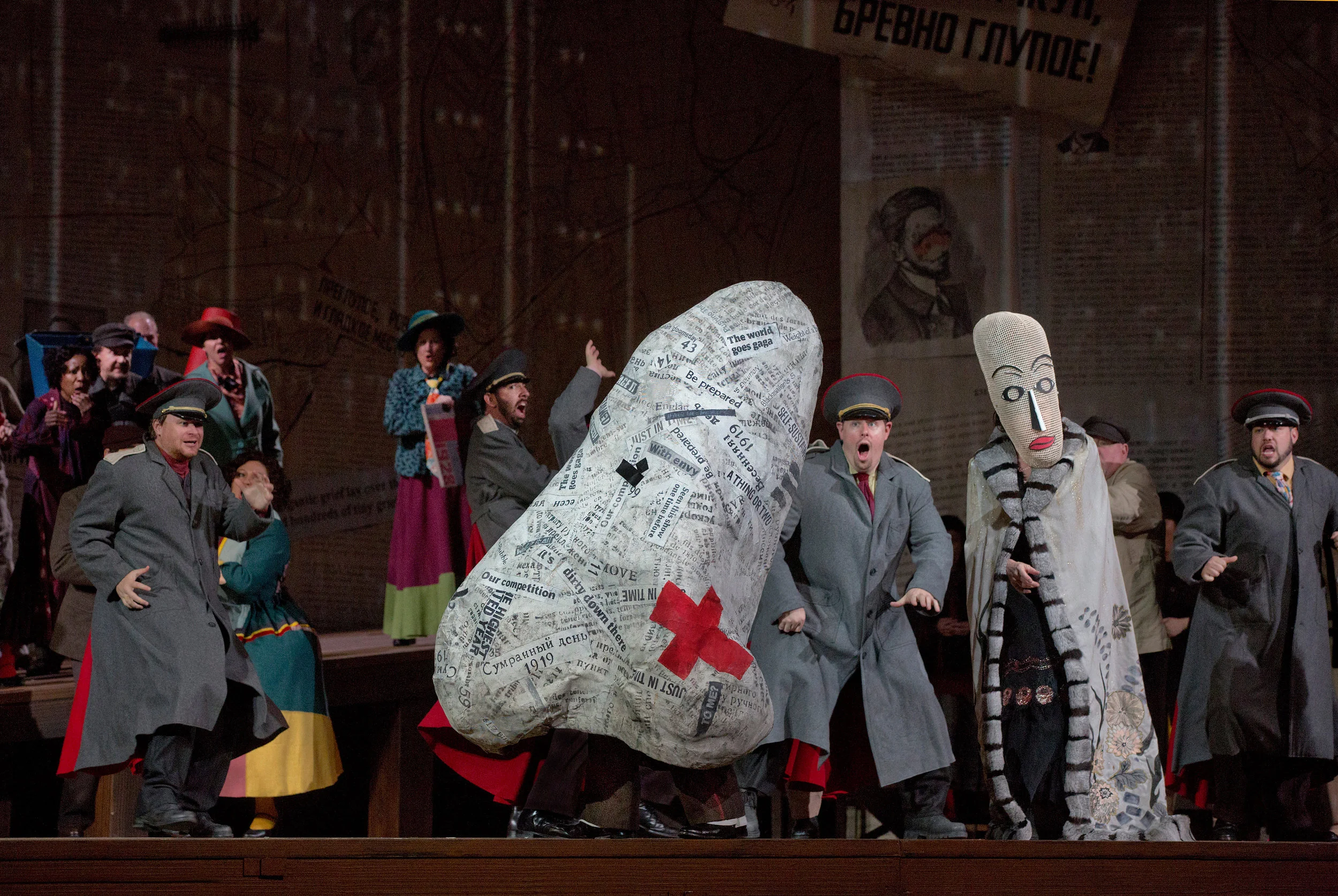

- Performative Listening: We always try to either do live demos or watch high quality videos. Noticing the performers and the audience—how they are placed, what they look like, how they're behaving, what they're playing—emphasizes the human agency of music, reveals cultural values, and adds visual interest to a sonic experience. (There's nothing quite like seeing a small bass drum player pounding away for the end of Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony and have to leap upon his instrument in the end to mute the sound!)

- Extra-Musical Listening: Words, costumes, backdrops, stories, expressions, pyrotechnics! Some genres (opera, character pieces, tone poems) revel in the extra-musical combination of media. Other genres (absolute symphonies and chamber music) go out of their way to try to avoid these things. Noticing either stance gives us more insight into cultural values and context.

- Cultural Listening: This is the backbone of Music 15 as I taught it. I always tell my students that the stories we discuss are only part of the complex story, but also that knowing about the context of a piece provides a frame of reference that can change how you hear it. Palestrina's beautiful a cappella masses go hand in hand with Counter-Reformation views of Catholicism's role as spiritual orthodoxy. Berlioz's creepy finale makes sense in a context of Romanticism and gothic novels. Schoenberg's twelve-tone compositions mesh with the cultural disillusionment in the wake of WWI and the advent of composition as an academic discipline.

Conductor/composer Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) directed the NYPhil's Young Person's Concerts from 1958-72, which were broadcasted on TV. Iconic.

Good luck Music 15! May future graduate students appreciate you (in all senses of that word).