I took my wife to the opera last weekend. #tophatandspats The Met Live broadcast series was playing Shostakovich's The Nose, and I simply couldn't pass up this unique but admittedly bizarre experience. We prepared ourselves by reading through Gogol's short story and I attempted to lay out the musical expectations of modernist Russia and young, pre-censorship Shostakovich. (Gogol Spoiler Alert: a petty bureaucrat wakes up sans nose, finds it out in society pretending to be of a higher social class, the nose refuses to return to its rightful place, the bureaucrat is distraught at the social injustice of it all, but wakes up a few days later with it returned.)

Family friendly fun! Who doesn't love a fantastical tale of bodily dismemberment and anthropomorphicization?

Nevertheless, we were sorely unprepared for what was in store. There are doubtless many studies and essays that have been written on the piece that might illuminate the work more cogently, but as a Soviet music enthusiast, and a musicologist who's given opera a fair bit of thought, here are a few of the things that stood out:

- The piece is challenging from a musical standpoint. It's helpful to remember that this is the era of the poet Mayakovsky who delivered his poems through a bullhorn, screaming. The declamation is utterly violent, perhaps unmusical (especially the sycophantic or schizophrenic laughter ["ha ha ha" "ха ха ха"]), and the instrumental interludes pushed me to the threshold of pain, in their percussive, repetitious crescendos. This is difficult to handle and it's even more difficult to notice variations within the sonic world that would give subtlety to the various characters or moods.

- This type of music is not intrinsically bad; it has its place and communicates its message at a visceral level that few musical languages can. (Thank you modernism.) I wonder what this medium does to the subject. Opera as a multilayered amalgam of music, literature, and visual effects is generically polyglossic—a Bakhtinian word denoting the simultaneous presence of multiple discourses. I find Shostakovich's music to be dissonant with Gogol's original story, a tale that I interpret as hinging upon "decorum"; in presenting that decorum, Gogol essentially exposes its ridiculousness and shallowness, but it has to be there in the first place before it can be critiqued. Shostakovich's musical world creates a sense of musical chaos, a world in which decorum is merely a concept ("You should know your proper place") that is completely at odds with the musical mode of expression, ie. atonal screaming.

- Without Gogol's restrained layer of subtle decorum (through which we see the delightful exposure of social folly), the opera feels monolithic and lacking in narrative drive. There is hardly any need for the main character, Kovalyov, to recover his nose. He already inhabits a world of bizarre relations, fragmented personalities, chaos barely held in check by some unseen social mechanism. Nothing essential changes when he recovers his body part. No decorous society (however empty and ridiculous) is resumed.

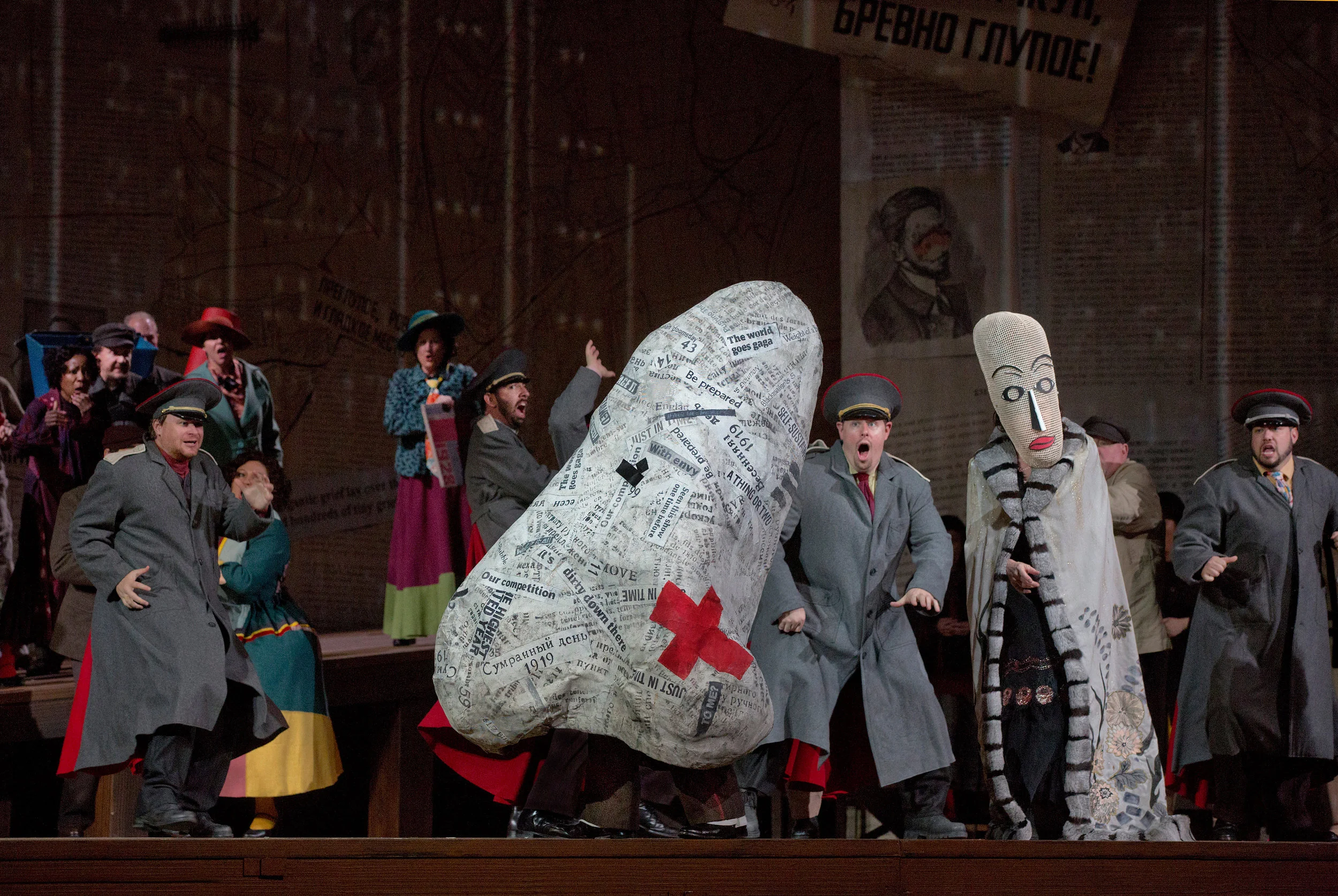

- This seems to be highlighted by the production choices of director, William Ketridge. He sets the scene in modernist, 1920s Russia (rather than in pre-Soviet, Imperial Russia, as Shostakovich envisioned), makes continual use of Monty Python-esque projections and visuals, and has several cast members inexplicably wearing masks worthy of Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon. If there is an order in this society, back to which an alienated outcast would desire return, it is completely covered up by the madness of visual cacophony. There is no impetus to return, no wholeness anywhere. (It was equally bizarre to have an actor lamenting the loss of his nose while no attempt was made to conceal it via makeup or prop at all.) In an of itself, the visual mastery was entertaining, but I found it to be extremely dissonant with Gogol's tale.

- Some musical moments were worth remembering and exploring further: The church scene was haunting and reminded me of the Coronation Scene from Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov. The mournful oboe music accompanying the futile attempts to reattach the nose (much like Peter Pan's fruitless attempts with his wayward shadow). And the balalaika-accompanied song of the valet, Ivan, which takes its text from Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov.

Picasso's Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), some of whom seem to be having their own Kovalyov sort of day.

I liked it, but would want to study the score a bit more before seeing it again, as that might make clearer the aural relationships within this stage society and open space for musical/social critique. Once again, my wife is a trooper. (Her husband has now made her sit through this AND Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire. I'd better take her to some Mozart quick!)

What do you think?