Happy Winter Solstice, everyone! As you can see from part 1 “The Hogwarts School Song” and part 2 “Recorder Squeaks,” the technique of analysis I am borrowing from the Harry Potter and the Sacred Text podcast can lead in unexpected directions. Within the fictional world of Harry Potter, music lies on both sides of the Muggle and magical worlds; it is simultaneously ordinary and enchanting. In this post we encounter the familiar scene (if only from period movies) of an instrumental ensemble playing ballroom dance music for an old fashioned party… but with a twist.

Human / ghost ballroom overlap in “Once Upon a December” from Fox Studio’s 1997 movie Anastasia with music by Stephen Flaherty and lyrics by Lynn Ahrens.

Once again I will examine a musically descriptive text from the Harry Potter series using a modified lectio divina sacred reading technique as outlined below:

Context: What is happening in the story when this excerpt occurs?

Musicology [NEW]: What might this music sound like and what ideas are associated with it?

Metaphor: What imagery or associations does this excerpt suggest?

Personal: What personal memories does this excerpt recall?

Action: What does this excerpt motivate you to do in your life?

Today’s passage is as follows:

“As Harry shivered and drew his robes tightly around him, he heard what sounded like a thousand fingernails scraping an enormous blackboard. ‘Is that supposed to be music?’ Ron whispered."

“The Deathday Party” by Dan Waring.

1. Context

We are now on pages 131-132 (US version) of the second book, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, Chapter Eight, “The Deathday Party.” Harry, Ron, and Hermione have been invited by Sir Nicholas de Mimsy Porpington (aka Nearly-Headless Nick), the ghost of Gryffindor Tower, to attend a party in honor of his five hundredth deathday on October 31.* Harry had felt compelled to accept this unusual invitation in light of the events of the previous day in which Nick, whose pride had been wounded by a rejection letter from the Headless Hunt, helped Harry out of a spot of trouble with Filch, the cantankerous caretaker. The next day Harry (bound by his promise), Ron (reluctant and hungry), and Hermione (enthusiastically inquisitive) walk past the doors of the Great Hall and the sumptuous smells and lively chatter of the Halloween Feast and make their way down into the dungeons. With every step they take, the temperature drops, engulfing them in an icy chill, their cloudy breath illuminated by ghastly black tapers on the walls which burn with a pale, blue light. They are greeted at the door of a large dungeon by Sir Nicholas himself, who solemnly ushers them into an incredible sight: “The dungeon was full of hundreds of pearly-white, translucent people, mostly drifting around a crowded dance floor, waltzing to the dreadful, quavering sound of thirty musical saws, played by an orchestra on a raised, black-draped platform.” In addition to this unusual ensemble and the spectral ballroom dancing, there is also a large table spread with a tombstone cake and rancid food. While overwhelmingly nauseating for the humans, ghosts can only hope for a mere suggestion of taste from this noxious fare as they pass their bodies – mouths agape – through the serving table. Lastly, perhaps most uncomfortable of all, this party has smalltalk!

*As I began writing and researching this post we passed through October 31, Halloween, or, to use its rather older name, Samhain (pronounced [ˈs̪ãũ.ɪɲ] in Scottish Gaelic). Marking the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter, this Celtic festival is also considered a threshold day in which the veil separating this world from the Otherworld was at its thinnest, allowing for a brief connection between the living and the dead.

2. Musicology

Photo of Marlène Dietrich playing Jacques Keller’s toothless “singing blade” around mid-1950s. She started playing the musical saw while shooting the film Café Elektric in Vienna (1927).

The musical saw is literally a hand saw, a sheet of tapered metal with a handle. This tool is transformed into an instrument when a sawist clamps the handle between their knees (teeth facing towards them), grasps the small end with the fingers of one hand or by means of a specially made handle, and draws a violin bow across the flat edge.* That’s the general idea, but to make the saw actually “musical” is a whole different story. To make a specific sound, the saw must be bent into an S-shape, which dampens the frequencies of the curved portions while isolating the frequencies made by the flat stretch or “sweet spot” in the middle. By bowing in just the right position, the result is a warbling but piercing tone that is often considered voice-like yet disembodied. By manipulating the saw into a larger or smaller S-shape and moving the sweet spot up or down to thinner or wider portions of the saw, a skilled sawist can produce higher or lower pitches. Here is Brigid Kaelin giving a great tutorial from start to finish. Because the saw can be bent at extremely small increments, the instrument is capable of playing a continuous glissando, a smooth gradation of pitches much like a human voice.** This means a musician must overcome the rather daunting task of learning to know precisely where their desired pitches lay within this smooth and unmarked continuum.

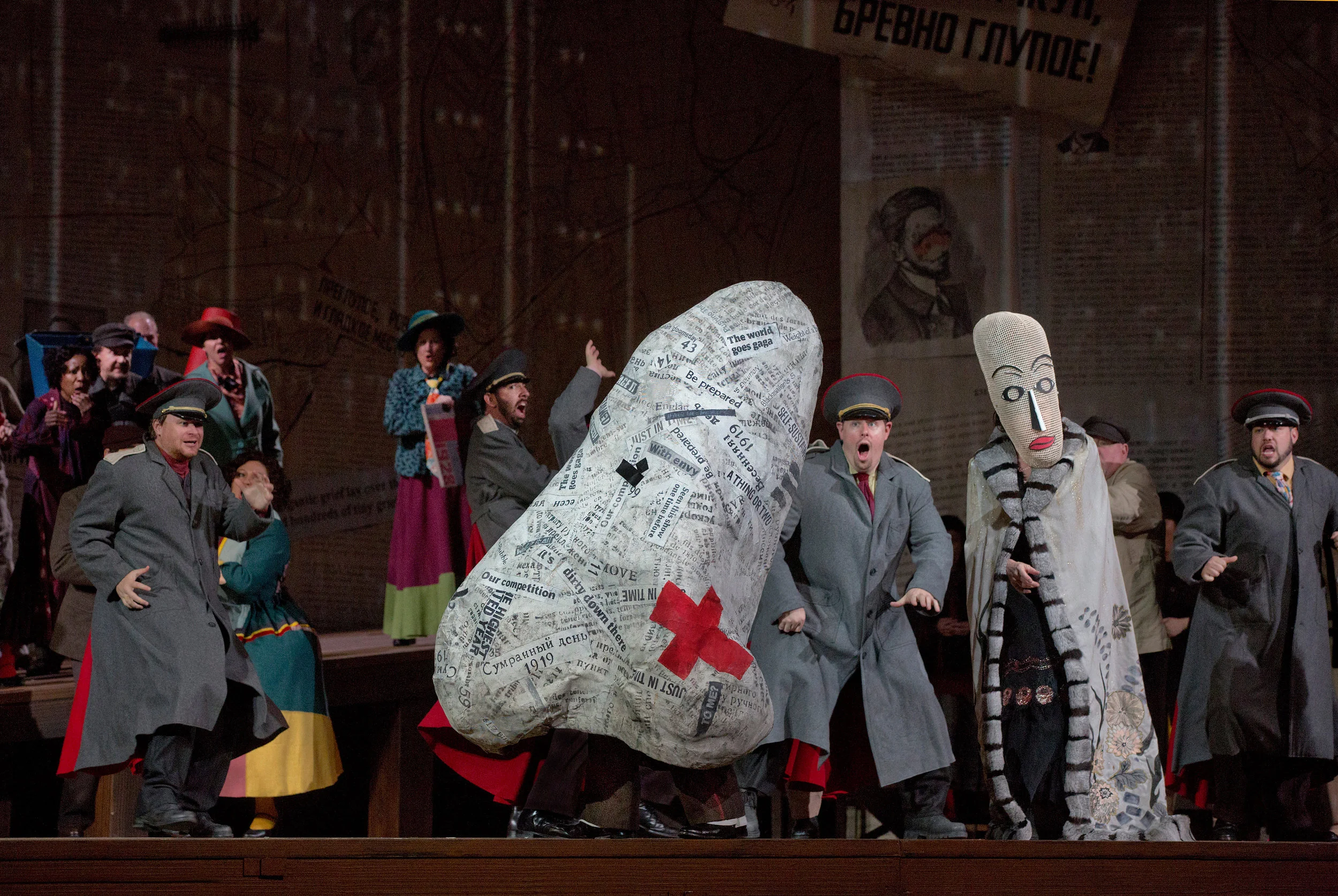

The musical saw seems to have begun first as a folk instrument (South America? North America? Scandinavia? who knows?), later entering into more widespread use around the turn of the twentieth century. It appeared in popular contexts such as vaudeville shows in the US, movie sound effects such as the song “Give a Little Whistle” from Disney’s Pinocchio (1940), and USO concerts during World War II. Additionally, classical composers took it up beginning in the 1920s, where it could function as a dramatically unsettling sound effect, as well as an instrument whose glissando allowed it to play experimental, quarter-tone music. In the former case, it appears as spectral wailing in the séance scene from Franz Schenker’s (1878-1934) opera Christophorus oder Die Vision einer Oper (1925-29), grotesquerie in Dmitri Shostakovich’s (1906-1975) satirical opera The Nose (1928),*** and the otherworldly ascension of the dying Sphinx in George Enescu’s (1881-1955) opera Œdipe (1936). In the latter case we have pieces such as De Natura Sonoris, No. 2 (1971) by Krzysztof Penderecki (1933-2020), Divination by Mirrors (1998) for saw and two string quartets tuned a quarter tone apart by Michael A. Levine (b. 1964), and Dreams and Whispers of Posideon (2005) by Lera Auerbach (b. 1973). The delightful dancer-turned-sawist Natalia Paruz seemingly straddles all genres, performing in concert halls, recording movie sound tracks, and busking on New York City subway platforms.

Flier for the 7th Annual New York City Musical Saw Festival (2009).

In general, musical saws are performed soloistically, either alone or with the accompaniment of different instruments, expressing a single, disembodied voice. But in the story, what really set Harry’s nerves on edge was the sound of thirty saws playing together, producing a multi-layered chorus of disembodied voices that create a shimmering wall of wailing sound. There are only several contexts in which we might encounter this unique phenomenon. One of those is at a festival, such as the 2009 New York Musical Saw Festival. At this event they set a Guinness World Record when fifty-three sawists performed Schubert’s Ave Maria. As you can hear, the players and the sound are enthusiastic and gregarious. Another method is virtually through digital duplication and layering, where a single sawist records themselves multiple times and layers the tracks together to make an orchestra. Examples include Chili Klaus, a Danish chili pepper connoisseur, performing a schnazzy duet of “When You’re Smiling” with himself, and Brigid Kaelin making a recording of herself thirty times over playing an arrangement of “Happy Birthday.” This last example was made specifically with Nearly-Headless Nick’s Deathday Party in mind, and is perhaps the closest thing available to get a sense of what the children heard in that dungeon.

One final detail complicates this musical event: the orchestra plays not as concert music or as background music, but as accompaniment for ballroom dancers. They are specifically performing a waltz, a type of dance that has become inextricably associated with formality, grace, and prestige. Countless ballroom scenes in movies – from The Great Waltz (1938) and Cinderella (1950) to Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011) and La La Land (2016) – create such an atmosphere as the dancers elegantly move in time to the steady 1-2-3, 1-2-3 of the music. Yet it is precisely the need for that steady rhythm that makes an orchestra of musical saws problematic. Unlike an instrument such as a violin or piano (which are both capable of sharp attacks when a thin string is set in motion by, respectively, a bow or a felted hammer), the musical saw has a slow attack and a more gradual blossoming of sound as the energy of the bow must travel the width of the metal sheet. I am doubtful that a musical saw could play with the kind of rhythmic precision necessary for a clear and crisp waltz. I am even more doubtful that an orchestra of thirty saws could do it, given the coordination required. Yet rather than point out a flaw in the story, I find this detail particularly interesting in light of my chosen metaphor…

*Handsaws have also been used in other musical genres, notably ripsaw or rake n’ scrape which originated on the Turks and Caicos Islands in the Bahamas. In this instance, the player scrapes the serrated edge with a metal object (usually a screwdriver or a butter knife), creating a rhythmic grating sound that can be altered by bending the saw. Here is musician Lovely Forbes giving an explanation and demonstration. And here’s the band Bo Hog and the Rooters playing rake n’ scrape music with saw performed by Crystal Smith.

**Other instruments developed in the twentieth century also employed this continuous glissando effect, and likewise filled a sort of experimental-novelty-otherworldy-spooky sound niche. Most notable is the theremin, an electronic instrument developed by Russian inventor Leon Theremin in the 1920s, and which is the de facto sound of spooky aliens and ghosts, as well as appearing in orchestral pieces, and covers of jazz standards. More recently, sound designers have Frankensteined new instruments such as Mark Korven’s Apprehension Engine that uses continuous glissando among other effects (such as the woeful tone of the hurdy-gurdy!) to create truly nightmarish sound worlds.

***In the score, Shostakovich indicates the use of a “Flexatone”. There is some question whether he and other composers from the 1920s onward meant a musical saw, which was understood as an instrument capable of “flexing or bending a tone” or a different tremolo-producing percussion instrument that was patented around the same time called a Flex-a-Tone. See the Shostakovich link for a fuller explanation.

3. Metaphor

I read the theme of dissociation in this excerpt.

Death is one of the most ultimate forms of detachment. Through death a profound and deep rift is driven between those who have died and those who continue to live, separating us from engaging in those activities that engender relational meaning in life – shared time, shared space – leaving us with fragments and echoes, memories, photos, recordings. While the Harry Potter series devotes a good amount of energy into grappling with the reality and finality of this mortal rupture, the ubiquitousness of ghosts seems to overcome it with magical nonchalance. Ghosts – pearly white, cold to the touch, able to float through walls – are everywhere in Hogwarts, and interact as a matter of course with the living, enjoying both cordial and heated conversation (Sir Nicholas and the Fat Friar), delivering deathly boring history lectures (Professor Binns), maintaining secrets (the Gray Lady), and engaging in warfare (the Headless Hunt).* It would seem that the presence and behavior of these ghosts go far in negating Death’s Sting.

But what exactly is a ghost?

A scene from “The Innocents” (1961), an adaptation of Henry James’ 1898 horror novella Turn of the Screw, where ghosts and childhood innocence spell disaster. “He was there or was not there: not there if I didn't see him.”

In the fifth book (Chapter Twenty-Eight “The Second War Begins”), Harry, consumed with the desire to circumvent death and reunite with his godfather Sirius Black, corners Sir Nicholas and strives to understand: “You died, but I’m talking to you… You can walk around Hogwarts and everything, can’t you?” Sir Nicholas, hesitant and shamefaced explains that “Wizards can leave an imprint of themselves upon the earth, to walk palely where their living selves once trod… But very few wizards choose that path.” Instead, the majority will have “gone on”. He continues, “I was afraid of death… I chose to remain behind. I sometimes wonder whether I oughtn’t to have… Well, that is neither here nor there… I fact, I am neither here nor there… I know nothing of the secrets of death, Harry, for I chose my feeble imitation of life instead.” The ghost Sir Nicholas, and by extension every other ghost who attended his Deathday Party, avoided the painful and frightening mystery of death. They opted for an existence of numbness, a feeble imitation that grasps for the faded shreds of life’s familiarity, yet continually (eternally?) fails to hold on to anything of substance. Ghosts are the embodiments of dissociation. And the details of this Deathday Party bring this strikingly to the fore.

For the humans, this congregation of ghosts is sensorially overwhelming. They are too cold to the touch. Too busy for the eye. Too nauseating for the nose and tongue. And too discordant for the ear. Harry describes the sound as “a thousand fingernails scraping an enormous blackboard,” a simile that is both tortuously chilling and vindictively intentional. Yet from the perspective of the ghosts, their dissociation from existence has numbed them. In their “feeble imitation of life” they seek extreme stimulation in an (ultimately futile) attempt to reconnect. For all their intemperate frigidity, they remain unable to feel and be felt. For all their glowing luminosity, they remain transparent and insubstantial. For all their noxious and putrid food, they experience not one soupçon of flavor. The orchestra of musical saws serves a similar function.** For all the wall of wailing sounds, perhaps the ghosts only catch the merest whisper of a melody, only feel the merest trace of a waltz rhythm. And for all their dancing – without touching one another, without feeling the connection of their feet to the floor – the delight of dance fails to enliven their souls. Ron’s question “Is that supposed to be music?” goes beyond his signature petulance at encountering the unfamiliar, and rather prompts us to consider whether music – those creative acts that bind humans into relationship with one another – is possible for ghosts.

*Ghosts are one thing, but people living beyond the grave in the form of portraits is another! Also, are the pictures in the Chocolate Frog trading cards sentient?

**It is possible that the pomp and circumstance of this party, including the musical saw orchestra, are also performative and symbolic. Sir Nicholas seems to be painfully desperate to appear like a successful ghost: prestigious, influential, learned, frightening. Even the physical characteristics of a musical saw speak to his desire to influence perception: music played by thirty serrated, toothy cutting tools certainly contrast sharply (pun intended) with the blunt axe that produced his botched beheading five hundred years earlier.

4. Personal

My current music room with Bruser’s book on the music stand. Ample opportunity to notice struggle and choose connection.

I am prone to dissociation. I learned from an early age that complex emotions and experiences could be dealt with through a certain level of psychological separation. As an adult I’ve come to realize that this strategy no longer suits me; as Brené Brown states in The Gifts of Imperfection (2010), “We cannot selectively numb emotions, when we numb the painful emotions, we also numb the positive emotions.” Knowing this about myself, I have ample opportunities to notice my avoidant reflex, and to consider truer and more whole-hearted actions. One such opportunity in which this happens is in my relationship to making music. I have been musicking in many ways over decades now, and while I can attest to what I would call a “golden thread” of genuine love between myself and my music making, there have been times when dissociation – from the music’s demands, from my emotional states, from life’s circumstances, etc. – have been a large part of my motivation. I can remember sliding onto the piano bench in order to create a wall of sound that signaled my familial or social unavailability, producing less of a musical experience and more of an accumulation of notes detached from meaning, my mind and body elsewhere.

It was not until later in my twenties that I came upon The Art of Practicing (1997), a book written by pianist, educator, and author Madeline Bruser that takes a soulful approach to exploring the potential for numbness. In the book she speaks about the musician’s propensity to valorize struggle. Playing music always involves eventual frustration, and many of us meet that frustration with the idea that we simply need to knuckle down and practice more, an activity characterized by repetitiousness, regimentation, and joylessness. Bruser wonders why we think such an arduous and authoritarian approach to music making in practice sessions ought to produce a musical performance filled with freedom, openness, and vivacity. Rather, she advocates for treating all musicking as an opportunity, first to notice our reactions to struggle. Do we move towards the mask of 1) overstated passion, 2) controlling aggression, or 3) expressionless avoidance? Second, we can take the time to pause, feeling the uncertainty and anxiety, and recognizing them as signs of our deep connection to ourselves as artists and as humans. And third, she suggests reengaging with openheartedness, vulnerability, and presentness. I very much appreciate this approach and its reminder of the value of music making as a profound act of connection, to the music, to ourselves, and to others.

5. Action

“Ghosting” in many ways feels like a proper response to a world that seems oversupplied with stimuli. The exhaustion that we all feel after years of doom scrolling through constant political infighting, environmental catastrophes, global diseases, social injustices, and mindless violence is truly real, to the point that researchers have coined the term Social Media Fatigue (SMF) in order to study it more closely, and papers are constantly being written on burnout in mothers, activists, educators, nurses, etc. How do we stay connected, yet protect ourselves from becoming overwhelmed? How might we utilize Bruser’s method for musical connection to carve out a selful and safe place for ourselves in other areas of our lives? How might we use this to cultivate wider networks of connection with others that bring music – both actual and metaphorical – to the world?

NEXT: Phoenix Song I…