Coming up on five years ago now, I wrote what was intended as the first in a series of posts on the intersections of music and J.K. Rowlings’ Harry Potter series, examined through the lens of the "Harry Potter and the Sacred Text" podcast. Much has happened since then. I for one finished dissertating and entered that magical time of post-doctoral soul-searching. My partner then began her own PhD journey in the area of Clinical Psychology; check her out here! The HPST podcast made an episode about every chapter from every book, started over from the beginning again with a new co-host, launched a “Women of Harry Potter” series, and soundly condemned Rowlings’ transphobic turn. And the world did a lot in that time as well. More and more Harry Potter movies of dubious quality keep coming out. Also global ultra-right politics is on the rise, as are the earth’s sea levels. Wars, coups, saber-rattling… Some grounding seems in order. It’s an opportune moment to return to this project.

Everything a hero needs.

As you can read from the first post on “The Hogwarts School Song” I will be examining a section of musically descriptive text from the Harry Potter series using a modified lectio divina sacred reading technique as outlined below:

Context: What is happening in the story when this excerpt occurs?

Musicology [NEW]: What might this music sound like and what ideas are associated with it?

Metaphor: What imagery or associations does this excerpt suggest?

Personal: What personal memories does this excerpt recall?

Action: What does this excerpt motivate you to do in your life?

Here we go:

[Harry] put Hagrid’s flute to his lips and blew. It wasn’t really a tune, but from the first note the beast’s eyes began to droop.

Mary GrandPré, illustration for “Through the Trapdoor” chapter (1998). Attention, chien bizarre!

1. Context

This passage is taken from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (US version, page 275), Chapter Sixteen "Through the Trapdoor" and describes an important moment in a tense situation: Harry, Ron, and Hermione, having resolved to foil Professor Snape’s (alleged) robbery of the Sorcerer’s Stone, have snuck out of their dormitories late at night and gotten into the forbidden third floor corridor. Here they encounter for the second time Fluffy, a giant three-headed dog owned by Hagrid, which has been kenneled behind a locked door for the duration of an academic school year. This terrifying, tripartite pup is the first in a series of obstacles put in place to protect the immortality-giving Sorcerer’s Stone, and stands guard over a trapdoor leading to hidden chambers below. Yet the three children come prepared; earlier that day they wheedled out of Hagrid the secret to the beast’s Achilles’ Heel: “Fluffy’s a piece o’ cake if yeh know how to calm him down, jus’ play him a bit o’ music an’ he’ll go straight off ter sleep.” Hagrid’s irrepressible penchant for divulging important secrets not only clues in the children, but had been communicated previously and inadvertently to (allegedly) Professor Snape, who could now use the information to bypass Fluffy and reach his prize. Upon arrival in the corridor, the three children see a harp lying discarded on the ground at the dog’s feet, clear evidence of the dark wizard’s machinations. Providentially, Hagrid had given Harry a whittled flute for Christmas that year, the perfect tool for such an important task, and within a few strains Fluffy is rendered incapacitated. The way is made clear for the children to plunge onward on their mission.

2. Musicology

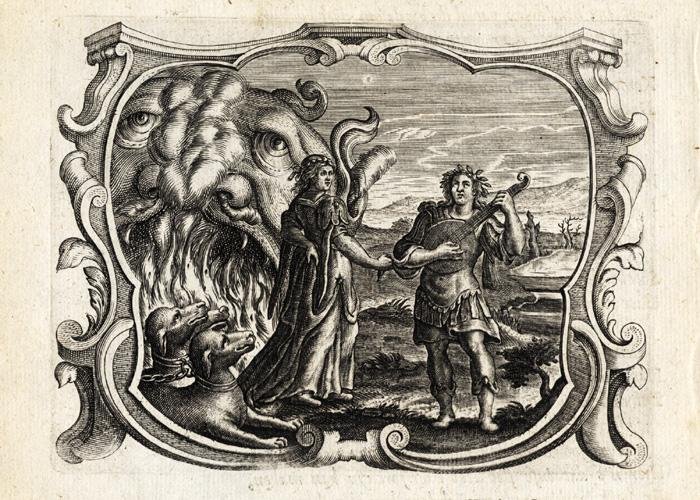

“Orpheus saved his spouse with the sweet sound of his Citharian harp” by Dutch Jesuit illustrator Johannes Bolland (1596-1665). Spoiler Alert: the story does not end quite so salvifically… Here Orpheus plays a 17th-cent. lute rather than a kithara.

The trope of music calming the savage beast has a long history in varied discourses on music’s supernatural, supraverbal, and suprarational power, touching on such lines of thought as mystical sacred rituals, political propaganda, and applied music therapies. For instance, both ancient Chinese and ancient Greek philosophers mused (pun intended) at great length upon the power of music, contributing to the establishment of the doctrine of ethos, which claimed that music had the ability to speak directly to human emotion, alter personal characteristics, and effect the physical body like a sonic gymnasium. Kings and educators, take heed! Furthermore, various myths attested to the playing out (another pun) of music’s fantastical powers. In ancient Greek mythology, Orpheus was a kitharode, a virtuoso player of the kithara (κιθάρα),* a type of lyre by which he attracted the submissive and gracious attentions of forrest animals, streams, trees, and even rocks. Most famously, he employed his musical skills to convince Hades, the god of the Underworld to reverse the death of his beloved Eurydice, having first musically overcome such obstacles as Charon, the cantankerous ferryman of the river Styx, and Cerberus, the giant three-headed dog to whom Fluffy owes so much.

In order to infiltrate the “underworld” of Hogwarts, the witches and wizards in this story incapacitate Fluffy with different musical instruments which resonate with (yet another pun!) the particular cultural and musical context of Rowlings’ magical-medievalist Britain. The conniving dark wizard chooses to use a harp. Harps have a long historical and mythical presence in Europe, with images of triangular instruments depicted in manuscripts and stonework from as early as the 700s, its importation from the east occurring earlier. Early Celtic harps were strung with horse hair or metal wire and went by a variety of names such as cruit, clàrsach, telenn, and telyn. An Irish legend speaks of Dagda, the chieftain and high priest of the divine Tuatha dé Danaan people who possessed a harp that could alter people’s minds and change the seasons. (Here’s a “Stringdom” YouTube channel video featuring the playing and speaking of Elinor Evans.) In Rowlings’ book, the children discover the harp discarded on the floor, simply a visual indicator of past musical activity. However, in the film they encounter the instrument standing upright on a foot, plucking out a sweet song automatically and without human, physical touch through a magical enchantment.**

The protagonists, on the other hand, use a flute to charm the trapdoor’s guardian. That Christmas, Harry had been gifted “a roughly cut wooden flute. Hagrid had obviously whittled it himself… It sounded a bit like an owl.” I would argue that the most likely type of flute in this situation would be an end-blown fipple flute. End-blown: the instrument is held by both hands pointing away from the mouth when played, the hands covering and uncovering finger holes to alter the pitch. Fipple: the player blows into a narrow windway or duct that directs their breath at just the right angle to split against a sharp edge (the blade or labium) and make a sound. These kinds of instruments are exceedingly common across the globe, including musical traditions such as the seasonal Norwegian seljefløte, the enormous Slovakian fujara, the mellow Native American plains flute, the circular-breathed Thai khuli, the double-barreled Balkan dvojnice, the one-handed Basque txistu, and even the most noble American Weenie Whistle. Hagrid’s home made, wooden flute reminds me of a Hungarian furulya I own, simply made from soft elderberry wood with six holes and a fipple on the underside. Traditionally such an instrument would have been made and played by peasant sheep herders. Just right for lulling a monster to sleep.***

*It is likely that this word derived from Persian sihtar, meaning three (si) + string (tar), which is the same origin of the Indian instrument sitar. Subsequently, we get many musical instrument words from kithara, including gittern, zither, and guitar. Here is a recording of an improvised song by Aphrodite Patoulidou and Theodore Koumartzis on a modern “Lyre of Orpheus” at the Seikilo Museum and Cultural Center in Thessaloniki.

**This gave the film’s composer John Williams the opportunity to compose the piece “Fluffy’s Harp”. (What will these Muggles think up next?!) The tradition of the self-playing instrument is common in mythology and folklore; for instance, Russian, Ukrainian, and Mari stories regularly reference gusli samogudy, magically auto-playing zithers, such as the story of “Most Noble Self-Playing Gulsi” that Prince Astrach manages to steal from the castle of Deathless Kashtshei.

***Alternative flute types (side-blown, rim-blown, panpipes, etc.) are comparatively more difficult to produce any sound at all, let alone a pleasant owl-like tone. Instruments such as the Colonial-era fife, Indian bansuri, Andean siku, Arabic ney, Japanese shakuhachi, and Mongolian tsuur all require an enormous amount of practice and the development of specialized facial muscles. #swol

3. Metaphor

I read the theme of preparation in this excerpt.

The Harry Potter series is in many ways a journey of growth. The “childhood” of the first three books – with their modest length, narrative forthrightness, and relatively simple characterizations – makes way for the “adolescence” of the final four books – longer, moodier, darker, more ambiguous – as they follow the growth of the main characters from age 11 to 17. As the stories progress we come to learn what the characters bring to each new challenge and how they utilize their skills, emotions, minds, and experiences. This is particularly true for the titular character, Harry Potter, who we find out comes uniquely prepared to confront and triumph over extraordinary foes. The realization, cultivation, and utilization of this power is one of the main dramas of the story, starting with Hagrid’s brusque “Harry, you’re a wizard” and culminating in the answer to the question of who is master of the Elderwand. In some cases, Harry realizes that he is naturally endowed with aptitude, such as his ability to skillfully fly a broom with no prior training. In others cases, it is Harry’s past that shapes who he is: perhaps his flying skills have much to do with his deceased father’s aerial accomplishments, encouraged by his godfather Sirius in the form of a toddler-sized broom stick when he was 1. The importance of Harry’s preparation becomes all the more intense when considering his life-or-death struggle with Lord Voldemort – “neither can live while the other survives” – whether the embodied face of Book 1 or the brutal terrorist of Book 7.

What prepares him for his encounter with Fluffy? Several important strands come together at this moment. First, he is armed with the friendship of Ron and Hermione (but not Neville), who bring their own skills and energy to the enterprise. Second, he has a wealth of information, wheedled out of Hagrid, gleaned from books, remembered from Chocolate Frog cards, overheard in eavesdropped conversations, intuited from the working out of facts. With this information he not only has a plan for getting past Fluffy, but also is fueled to desperate, heroic, white-hot action. Third, he has the support of magical items, most importantly his father’s invisibility cloak, which was returned to him with the timely encouragement to “use it well,” as well as a wand to open locked doors. And fourth, he has the benefit of previous experience sneaking through the castle in the dead of night.

Major Pied Piper vibes happening here!

But one important aspect of Harry’s preparation goes without mention, a skill that, had he not possessed it, would have spelled complete and utter ruin. I’m talking about Harry’s musical training! Think about it. The only way to survive not being mangled and devoured by a three-headed beast is to “play him a bit ‘o music.” So he picks up a whittled flute almost as an afterthought, stands in front of the voracious creature, takes a breath, and plays. True, “it wasn’t really a tune,” but whatever it was had enough musicality in it to render the animal incapacitated. Imagine yourself in that situation. Could you have done that now? Could you have done that as a sixth grader? If so, where did you learn to properly hold a flute? To cover the holes? To know the fingerings well enough to get out some notes? To have diaphragmatic breath control to play soothingly and not squeakily? I would venture that your success is almost entirely due to your preparation because of recorder class in elementary school.* The recorder is an end-blown fipple flute with eight finger holes and a tapered bore, first documented in Europe during the Middle Ages and reaching its apex during the Renaissance and Baroque eras. In America, if you played one in third or fourth grade, you probably played a plastic one; if you were fancy it may have been a transparent plastic in a vibrant color! The unfortunate stereotype of recorder class, at least in America, is that of a squeaky, shrill, cacophonous melée, traumatic for teacher, student, audience, and instrument alike. Yet it seems that Harry was paying attention in class. He possessed enough skill to pass a very high-stakes test with Fluffy in the third floor corridor. Few would think of “Hot Cross Buns” as preparation for vanquishing a magical obstacle, yet without it, our heroes would have been utterly lost.**

*It should be mentioned that Hermione takes over for playing from Harry, suggesting that she too had the previous training at her Muggle primary school. Additionally, Harry seems to have had some sort of vocal training because he grabbed the flute merely thinking “he didn’t feel like singing.” I can’t see him singing freely at the Dursleys despite Vernon’s appreciation for “Tiptoe Through the Tulips;” perhaps his school had a children’s choir?

**Few of us got to experience the recorder’s full potential in elementary school. But it’s not too late! Grab your recorder wherever it is and learn to play “Hedwig’s Theme” from the YouTube tutorial of the fabulous, engaging, and accomplished Sarah Jeffrey of Team Recorder right now! It just might save the world! And to hear what another professional recorder player can do, check out Anninka Fohgrub in the Bremer Barockorchester’s performance of Georg Philipp Telemann’s Concerto for Flute and Recorder in E minor. The Presto finale at 12:38 is one of my all time favorite pieces!

4. Personal

Recorder class was not offered in my elementary school growing up. California is particularly notorious for its lack of support for arts programs in public school. As this January 2022 EdSource article by Louis Freedberg explains, despite state law requiring schools to provide “instruction on dance, music, theater, and visual arts,” these programs are inexorably dying, marginalized in favor of quantifiable subjects such as math and reading, and eviscerated by COVID restrictions. Low-income schools are less likely to be able to support arts programs, leading to wide socio-economic and racial disparities concerning which children engage regularly with art in the course of their early education. Perhaps this year’s Initiative No. 21 “The Arts and Music in Schools - Funding Guarantee Accountability Act” can help turn the tide. Rapper and producer Dr. Dre, a supporter of the measure, explains, “I’m all in on giving kids more access to music and arts education because creativity saved my life. I want to do that for every kid in California.” What might regular access to the arts do for all the state’s children?

Yours truly at (maybe) 6 and (maybe) 12. Probably the same plastic Yamaha soprano both times!

Even without recorder class at school, I actually did learn the recorder, but at home. I grew up in a musical family and an activity like playing a recorder in my bedroom seemed extremely normal. I remember playing (alone) through a book of duet arrangements of Anna Magdalena Notebook pieces by J.S. Bach. What better way to engage both body and mind in technical challenges, sometimes even encountering beauty? Could I have guessed that my efforts were in any way preparing me for something? By all accounts, no. Looking back, however, I can see that playing the recorder did prove foundational for me, laying the groundwork for my life’s richly multifaceted journey in music. The recorder led me to the piano and then beyond that to other instruments and sounds and people and courses and books and conferences. And I have taken many opportunities to return to the recorder even now, performing on it in the Folk Orchestra of Santa Barbara, giving live demos in college survey and history courses, and writing about it in blog posts on Harry Potter.

5. Action

We never quite know what will be important as we grow through life. What ought we focus on? What should we do with our precious time and energy? The world will tell you, of course. There are so many voices vying for authority, so many experts telling us how we measure up or fall short. From standardized tests to growth charts; parents, pastors, principals, and police officers; from guidance counsellors to Tik Tok influencers. We all want to be prepared, to feel that we have done whatever we should have done to be safe, successful, happy... To avoid disaster. But what if we had a wider belief in what being prepared for life meant? What kind of preparation from your life’s past have you received for life’s present? No matter how marginal. No matter how childish. Are there any surprises? How might we be more open to trusting that we are right where we need to be, learning what we need to learn, doing what we need to do? What would that do to the way we fill our time, treat our children, structure our societies?

NEXT: Ghosting Music…