Alright. Here we go!

For the first musicological analysis of Mumford and Sons music we'll take a look at the first song from their first album, Sigh No More. As stated in the introductory post, these explorations consider the music from a variety of angles in order to tease out instances of musical communication. This initial foray considers the combined effects of word and music as they progress through time.

I'm going to take some time to really dig into the lyrics of the song in this first post. This won't necessarily happen each time, but I think it's a good idea for three reasons:

- Most readers are probably more familiar and comfortable with analyzing words for their meaning or meanings (poetic exegesis, if you will),

- Having a solid foundation in the text will help us to understand how the music works with or against that meaning, how it relates to the semantic meaning of the words, and

- The eventual musical argument I'm trying to make will be important for future analyses, so going slowly now will give us a leg up later.

I won't always provide the written out song texts in their entirety. In some cases, ambiguities in the words provide opportunities for multiple meanings in their interpretation and is part of what makes the song so interesting. I'll actually be arguing that ambiguities in the words make them more musical, but that's jumping the gun... When considering the lyrics of Sigh No More, there is actually something of a problem in nailing down the "official" text; a quick search online reveals a plethora of contrary variations that drastically alter the meaning of the poem from one version to the next. The version I'm writing out here is the best one that I can come up with, based mostly on my own ears and aided by a little Shakespeare. Here it is, divvied up into three sections:

I've divided the words into three sections, basing this division on rhyme schemes, meter, and poetic meaning. By grouping the words in this way, we can see the tenor or feeling of the text change from one section to the next.

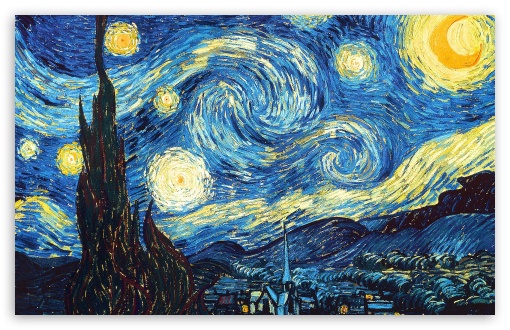

"Much Ado About Nothing" by Robert Smirke (1753-1845) via Royal Shakespeare Company Collection. Dogberry seems on edge.

In section A, I've underlined the lyrics that are quotations from Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing: "Serve God..." are Benedick's words of comfort to a dejected and wrathful Beatrice (Act V, scene ii), "Live unbruised..." comes from the concluding denouement where almost all character relationships are healed either through brotherly forgiveness or marriage (Act V, scene iv), and "Sigh no more..." is a fragment from a longer song that takes as its theme the infidelity of men ("deceivers ever") and the need of women to shrug off their defects ("by you blithe and bonny") (Act 2, scene iii). These quotations are not only plucked out of their theatrical context (while retaining some of the narrative associations for those who know where they come from), but are combined or sandwiched or mixed in with original lyrics by Mumford and Sons, which create interesting layers of reference and meaning.

What I mean by reference is what I perceive to be an ambiguity in who is speaking/singing the words at any given time. In the first stanza of section A, we hear a quote by Shakespeare, then an original line, another Shakespeare, and more original lyrics. The original words strike me as powerfully subjective and personal, as if uttered by a narrator, perhaps a narrator who is reading or listening to or recalling these lines by Shakespeare. This reflection upon someone else's words causes the narrator to insert their own commentary, and a desperate commentary it seems to be, judging by the repetition of "I'm sorry". Apparently Benedick's forgiveness does little to alleviate the narrator's conscience, but rather intensifies the feeling of guilt.

Again, in the second stanza of section A, Balthazar's song gets only two lines in before it is interrupted by the narrator who seems to identify only too closely with the culpability and fallenness of mankind, twice declaring "you know me". (Who this "you" actually is is a fascinating question!)

So, already this song has set up an interesting tension between a preexistent text and reactive commentary. Shakespeare is known as being an authoritative observer of human character, and it all seems to be too much for the increasingly despondent narrator.

The B section is short and unassuming, but actually functions as an important pivot point in the trajectory of this text. Another Shakespeare quote, "Man is a giddy thing" sums up Benedick's assessment of his own development, his changing character and priorities (Act V, scene iv). This time the narrator has nothing to add. Instead, the quote echoes not once, not twice but four times total! Repetition is very important in poetry and in music. The lyrics repeatedly declare that man is "giddy", a fun word that has roots both in "insanity" and in "being possessed by God". Benedick means here that he is duplicitous, a confirmed bachelor throughout most of the play finds himself recanting his views in the end and turning husband. Human changeability perhaps isn't all together a bad thing. Perhaps our very ability to change offers us escape from our sorrow, our impurity, and from the exposure we feel at being known and recognized as such.

Perhaps those are some of the ideas that are bouncing around the narrator's head, because as section C starts, we have moved into a very different world.

No longer quoting Shakespeare, here the contortions of the first section and the hammering of the second section give way to lyrics bursting with love, freedom, growth, alignment, beauty, and redemption. Interestingly the text does not seem to declare a happily-ever-after scenario, but simply, yet powerfully, speaks of new perspectives on the world and of choices to become "more like" that which we were designed to be. Perspectives have changed: the narrator now seems to be the one being addressed (perhaps by the knowledgable "you" that so frightened the narrator in section A?). The second stanza gives the mic back to the narrator and reveals their new understanding of the connectedness and potentiality of existence. We've come a long way.

Let me know how you think about this analysis of the poetry. I'd be happy to entertain other interpretations. Next time we will see how this lyrical trajectory plays out when put to music.