Even while school activities have continued to mount (classes starting at Westmont, finals nearing for UCSB summer session) I've continued to ride the sweet, sweet wave of fairy tale criticism that has been become nothing short of a hungry passion. This has been expressed particularly through interaction with the research-collaboration-project blog Subverting Laughter, a truly wonderful chapter-by-chapter exploration of MacDonald's Light Princess from a variety of angles and approaches. I've also been reading Jack Zipes' Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion which is challenging and thought-provoking at every page. I originally picked this one up for it's chapter on George MacDonald, but, now that I'm going through it from the start, it's amazing to consider the broader, cultural ramifications of fairy tales in terms of how they "civilize" people, or teach them to acceptably integrate themselves into society.

Doré's illustration for Perrault's Le petit chaperon rouge.

One of the themes that has jumped out at my through these activities is the symbolism of the wolf, its uses as a villain, as moral watch-dog, as devil, as splanchnon, and as a symbol for ravenous, devouring hunger. Here are some thought-provokers from this past week:

Zipes, Chapter 2: Setting Standards for Civilization through Fairy Tales: Charles Perrault and his Associates:

- (Talking about "Red Riding Hood" in its earliest, oral, folk tale manifestation, before Perrault used it for his own cultural purposes.) The brave little peasant girl, who can fend for herself and shows qualities of courage and cleverness... proves that she is mature and strong enough to replace her grandmother. This specific tradition is connected to the general archaic belief about witches and wolves as crucial for self-understanding. Hans Peter Duerr has demonstrated that "in the archaic mentality, the fence, the hedge, which separated the realm of wilderness from that of civilization did not represent limits which were insurpassable. On the contrary, this fence was even torn down at certain times. People who wanted to live within the fence with awareness had to leave this enclosure at least once in their lifetime. They had to have roamed the woods as wolves or 'wild persons'. That is, to put it in more modern terms: they had to have experienced the wildness in themselves, their animal nature. For their 'cultural nature' was only one side of their being, bound by fate to the animallike fylgja, which became visible to those people who went beyond the fence and abandoned themselves to their 'second face'." In facing the werewolf and temporarily abandoning herself to him, the little girl sees the animal side of her self. She crosses the border between civilization and wilderness, goes beyond the dividing line to face death in order to live. Her return home is a more forward as a whole person. She is a wo/man, self-aware, ready to integrate herself in society with awareness.

MacDonald, Photogen and Nyctaris:

- Watho: There was once a witch who desired to know everything. But the wiser a witch is, the harder she knocks her head against the wall when she comes to it. Her name was Watho, and she had a wolf in her mind. She cared for nothing in itself -- only for knowing it. She was not naturally cruel, but the wolf had made her cruel. She was tall and graceful, with a white skin, red hair, and black eyes, which had a red fire in them. She was straight and strong, but now and then would fall bent together, shudder, and sit for a moment with her head turned over her shoulder, as if the wolf had got out of her mind onto her back.

Padel, In and Out of the Mind: Greek Images of the Tragic Self:

- In darkness we see what we cannot see in light. Darkness is the unknown... Darkness is where we are most likely to encounter gods. And where we meet their prophets... Fundamental to Greek ideas of prophecy, and of the mind, is the idea that knowledge can be found in, and from, darkness... Like the Sirens' song, passion is destructive but illuminating.

And just because it sprang to mind, Mumford and Sons, Whispers in the Dark:

- You hold your truth so purely,

- Swerve not through the minds of men

- This lie is dead

- This cup of yours tastes holy

- But a brush with the devil can clear your mind

- And strengthen your spine

- Fingers tap into what you were once

- And I'm worried that I blew my only chance

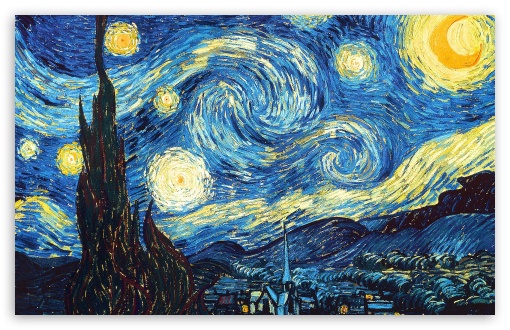

Van Gogh's The Starry Night (1889)—all a swirl.

The way of talking about the wolf in these contexts reminds me of Ruth Padel's investigation of the splanchnon: as a place of blackness; the embodiment of emotions, hunger, personality; the crossroads between beast and god... I feel like we don't have characters like this anymore... Maybe Gollum, or Severus Snape... There is a contradictory loss of innocence and gain of awareness and strength... And the witch Watho consumed and lost to the wolf within herself... the awakening of hunger and power, but the need to overcome it... Jack Zipes continues to show how fairy tales, from Perrault to Disney, have continued to try to downplay the presence of the wolf, the need to contend with it, favoring instead a wholesale suppression of all that could potentially ruin us and threaten society's stability... Our culture continually downplays psychological therapy, one of the few remaining arenas where we are given room to contend with our inner wolves... Paul Angone in 101 Secrets for Your Twenties points out that those who don't deal with their wolves and grow out of them, tend to grow into them... With Watho-like results?...

And how is music wolf-like? St. Augustine explores music's discomfiting and otherworldly beauty, "a certain sound of joy without words, the expression of a mind poured forth in joy..." Does/can/should music also be poured forth in the emotion of the wolf? Can music provide a relatively safe place to explore these realms? And what music?

What do you think?