After reading this article on BBC Mundo by Alejandro Millán Valencia a few weeks back, I’ve had the pleasure of encountering the musical artist LENIN, stage name of Lenin Tamayo, the 23-year-old Peruvian singer who is at the forefront of Q-Pop (Quechua Pop). Having embraced K-Pop (Korean Pop) as a source of camaraderie as a marginalized youth in school, he now combines that genre’s sounds and aesthetics with Peruvian elements rooted in traditional, indigenous Andean culture: clothing, dance, customs, and the Quechua language.

Photo Source: https://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/peruvian-singer-aims-to-introduce-q-pop-/7231045.html

According to a 2021 AP News article by Franklin Briceño, the Quechuan language lies at the center of long-standing tensions in Peru that have social, economic, and ethnic ramifications. Quechua had once been the lingua franca of the Incan Empire, but following Spanish colonization it became heavily discriminated against, outlawed in the 1780s following an indigenous uprising and intensely villainized during the atrocious civil war that began in the 1980s.* This prejudice has persisted and intensified to the point at which today Peruvian Quechua speakers have internalized “linguistic shame,” a mechanism that Ingrid Piller states is directly linked to the normalization and acceptance of oppression.** For this reason, LENIN’s macaronic songs, featuring lyrics in both Quechua and Spanish are a significant expression of cultural identity, a counterargument to the current state of the language and culture which celebrates love and fun, self-expression and cultural roots.

The song ¿IMAYNATA? hits a lot of these themes. The verses in Spanish drip with swagger and self-confidence, declaring in a declamatory style, “I live without fear of walking / Only love and freedom,” and “I tell you in Spanish, in Quechua, or in English / the language doesn’t matter one way or the other” (translations are mine or Google Translate). The pre-chorus in Quechua, however, is a slow build in a higher vocal register, resonating with a gnawing doubt, “What are you looking at / When your heart is dead?” The chorus, still in Quechua, has few words, all confidence, answering the question “¿Imaynata? [How do you do it?]” with syncopated exclamations of “¡Yoa!” and “¡Walk!” weaved through a somewhat pirate-esque riff.***

Valencia’s BBC article includes an interview in which Lenin expresses some of his views on singing in Spanish versus Quechua. He says that a language like Spanish is full of innuendo and double meanings, offering more room for hypocrisy. Quechua, on the other hand, has less equivocation and is more direct in the way that it connects the speaker to the world. In Lenin’s view, this means that a Quechua speaker has first-hand contact with emotions and nature. This comes across in the song KUTIMUNI which contrasts distorted, mechanistic, or anxious sections in Spanish with sudden shifts to luminous and tranquil parts in Quechua where one can almost hear the whisper of birdsong.

Photo Source: https://www.behance.net/gallery/144071069/Inca-Kola-Murales

Perhaps the most summational demonstration of the message of indigenous cultural revival and celebration is the song INTIRAYMI (which happens to be my childen’s absolute favorite to sing with and dance to). The title translates to “Sun God Festival” and is in reference to an Incan festival that celebrated the winter solstice, which has since been revived in several South American contexts. Lenin taps into the joy of this festival with a rousing Spanish/Quechua chorus: “It’s Inti Raymi / Let’s go dance / It’s Inti Raymi / Let’s go dance / Because the night is young / Everyone sing / Because life is one / It’s a festival!” His music video goes further with images of the sun / Inti, the offering of sacred cocoa leaves, performances of the ancient scissor dance mixed with modern break dancing, Aya Huma masks, a mural by Adriana Hiromi and Jade Rivera in the Barranco district of Lima that declares “Hagamos un Perú que nos dé gusto [Let’s make a Peru that gives us pleasure]”, and a crowd of young and excited people celebrating in the streets.

I’m still discovering the riches of LENIN’s music and especially look forward to exploring it with my children who can’t seem to get enough… Cuando Estoy Aquí and AMARULLAQTA deserve a listen. It also has me wondering about genre hybridity and minority languages. While a conservative approach to the matter of music + minority language tends to stick to strictly traditional styles, futuristic approaches consider how old and new might be combined to create something thrillingly alive. While some genres seem to require linguistic conformity to English, others seem well suited to and even encouraging of linguistic variety. Afterall, the genre of K-Pop (Korea) interacts not only with Q-Pop (Quechua), but also J-Pop (Japan), C-Pop (China), and T-Pop (Thailand). And heavy metal’s proclivity for sub-genrification and theatricality provides lots of room for linguistic variation; Swiss folk-metal band Eluveitie sings some of their songs in Gaulish, a nostalgically dark / darkly nostalgic act of cultural revivification. Perhaps there are other ways that hybrid genres can encourage singers in minority languages to imagine a future where, to quote LENIN’s song INTIRAYMI, “the sun comes every moment ever closer.”

*Briceño’s article mentions an interesting incident in which Peruvian Prime Minister Guido Bellido delivered a speech to Congress in Quechua, prompting some strong reactions from those in power who largely could not understand him. Translated, his message was equally stinging: “We have suffered for five hundred years. We walked slowly through hills and snowy peaks to arrive here in Congress, and have our voice heard… It’s time to change. It’s time for all of our country’s residents to look at each other as equals, without discrimination.”

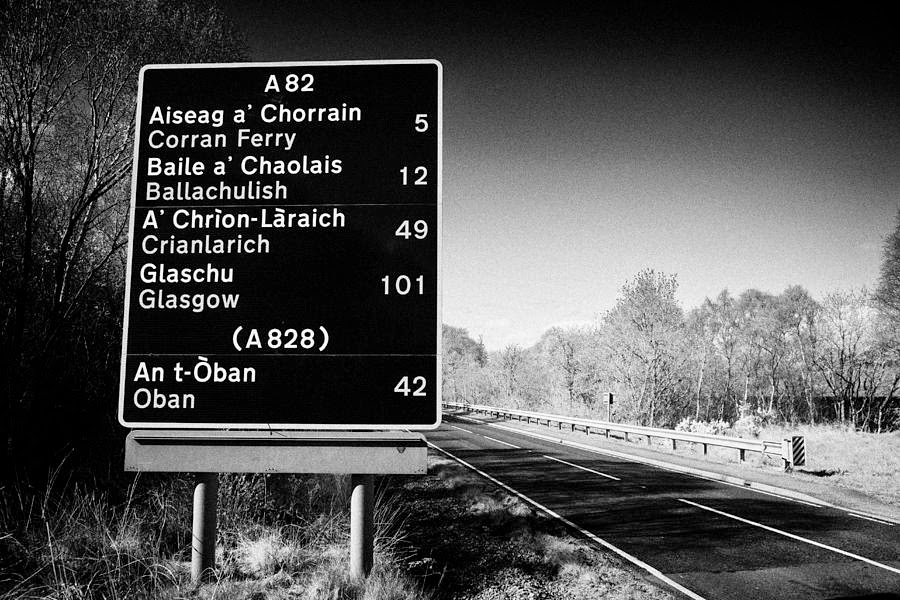

** This pattern of dehumanization is all too common in historical narratives of colonizers attempting to erase the culture of the colonized, often through linguistic shame taught to children in (often forced) school settings: Scottish Gaelic in the UK, Tahitian in French Polynesia, all Native American languages in North America, Spanish in California, etc.

***This is the song that instantly became a favorite of my kids as the chorus is very easy to sing and has such a sweet groove. Plus the Quechua word for “walk” is “puriy,” which we initially mistook for “booty,” and who wouldn’t want to shout that out while driving in the car as an elementary school kid?