Kicking off a rather full spring / summer of academic conferences, I attended a The Child and the Book conference May 15 through 17 in Podgorica, Montenegro.

Conference

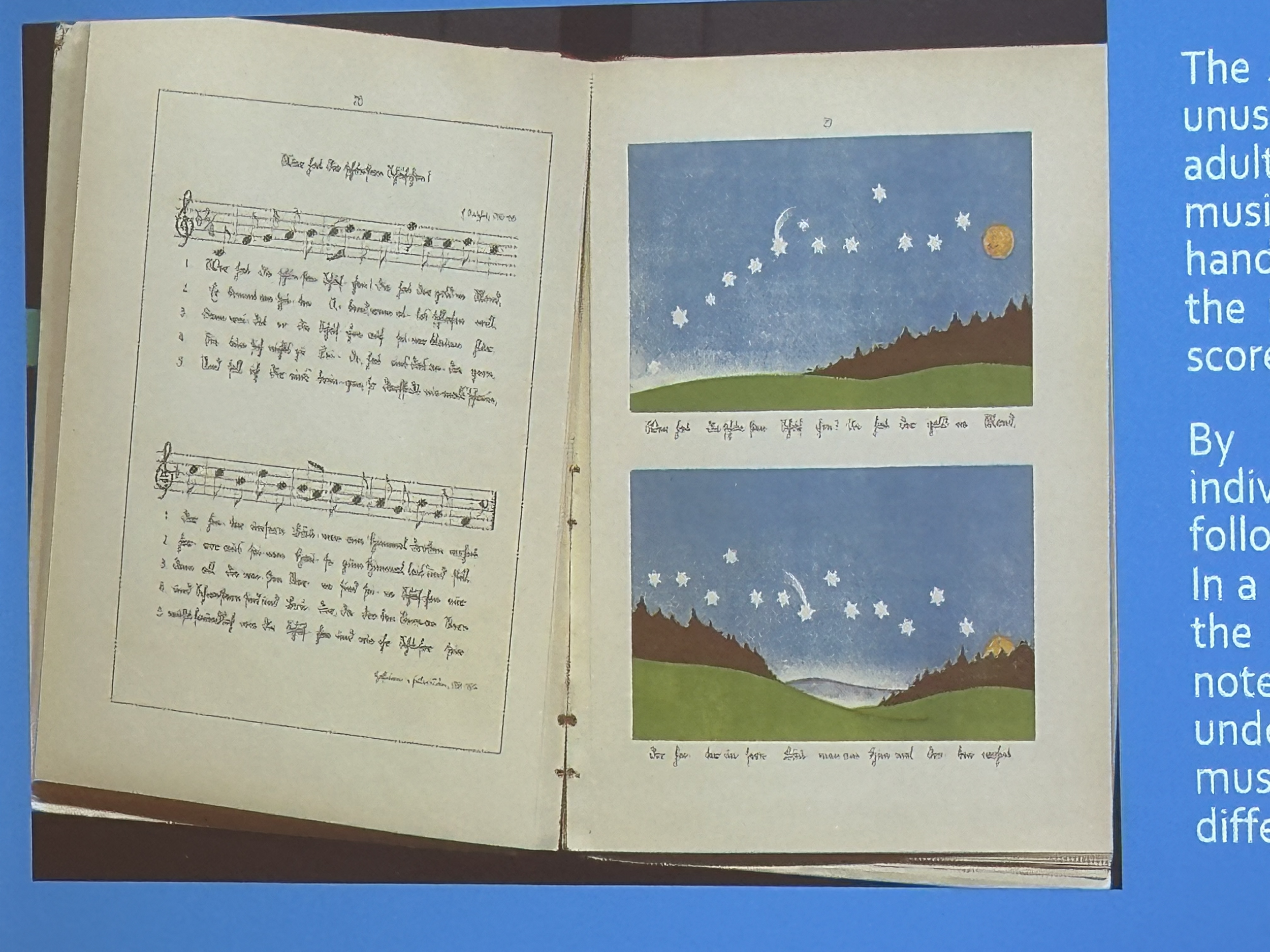

This was my very first experience with The Child and the Book, an international conference launched in 2004 that provides a forum for the exchange of scholarly research on all things pertaining to children’s and young adult’s literatures. While I enjoy hearing talks on all manner of subjects, as a musicologist in children’s literature conferences I normally have to do a fair amount of sleuthing in order to find presentations that deal, however obliquely, with music. Not so this time, as the theme was The Magic of Sound: Children’s Literature and Music. I had the pleasure of experiencing a wide range of papers on things as diverse as the many musical afterlives of Lewis Carrol’s “Jabberwocky”, musicalizations of masculinities in Disney’s Hercules, analyses of the ear-worm song “What does the Fox say?”, childism in Javanese children’s songs, film adaptations of Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, a close analysis of Fosse’s picturebook The Fiddler Girl, post-WWII pedagogical texts with fanciful illustrations that mirror (and are meant to teach) sheet music notation, gendered power dynamics in Disney ballroom dance scenes, and the sonic significances of Milton’s Paradise Lost. My own presentation “Casting the Spell: Musicalizing Fairytales and Märchenfrauen in Imaginative Children’s Music” took a look at the overlap in social and aesthetic significance between domestic piano music and literary fairytales, using examples of works by Renaud de Vilbac, Genady Osipovich Karganov, and Hans Huber. It was particularly fun to use a quotation by the indomitable scholar Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer and then to chat with her about it afterwards! They also have a great early scholars collective called the Grow Reading Group that did a thoughtful and interesting session that connected academics navigating academia in the beginning stages of their careers.

One of my favorite presentations – “Female Fury in Picturebooks” by Rosalyn Borst – drew a line between the emotional expressivity of punk rock Riot Grrrl music and the Dutch picturebook Sofia en de Leeuw by Pelaez-Vargas, posing questions regarding the limits placed upon emotions, particularly “negative” ones like fury, when it comes to adolescent girls. This talk inspired me to consider whether music exists that offer young children (boys and girls) an opportunity to express their anger, not merely manage it or negate it. In my own research, publishers carefully controlled nineteenth-century piano character pieces to establish appropriate social and moral boundaries in instrumental music that might otherwise give children license for raw emotion; a piece that could be understood as “angry-sounding” due to its key, rhythms, dynamics, etc. would need to be specified through a descriptive title like “The Tempest” or “The Naughty Boy”. Outright naming and expressing fury does not appear to be a theme of children’s music today. Though one avenue seems hopeful: heavy metal music for children is absolutely a thing! A group like Hevisaurus from Finland has a lot of potential for releasing the child’s roar. Can you think of any songs for children that give vent to anger through the lyrics and/or music?

The crowning event took place on the final night of the conference in a crowded downtown bar. There we came face to face with the magic of sound itself as conference organizer and superhuman Svetlana Kalezic Radonjic mounted a stage with her rock band and sang for about four hours without a break. There’s nothing like a late-night rave to shatter your image of academics as boring and stuffy pedants. Dance moves were seen that cannot be unseen! It was an unbelievable amount of fun!

Locale

Another first for me was traveling to the Balkans. I stayed in a hotel called Carine in the middle of town, just around the corner from a wide space called Independence Square and the conference venue, the National library Radosav Ljumović. Although it rained quite a lot during my stay, I took time to explore the city of Podgorica on foot, particularly noting the unkempt, green wildness of nature, which contrasted strikingly with both murals and graffiti. In fact, “contrasts” seems a fitting word for the city’s kaleidoscopic sights as it transitioned almost seamlessly from fifteenth-century Ottoman alleys to Soviet brutalist apartment buildings, and from flowing rivers lined by lush forests to seedy pawn shops. At one point I saw within a single glance a combination of make-shift (aka sketch) carnival rides set up in a parking lot, the eccentric stone towers of an orthodox church, and the distopic shapes of Blok 5. Upon closer inspection of the church, the Orthodox Temple of Christ's Resurrection, I saw the beginning of a wedding taking place, as well as a group of local musicians ready to celebrate afterward with a drum and various brass instruments. The hotel included a generous breakfast – scrambled eggs, cheeses, meats, olives, salads, coffee – and I am now obsessed with a particular type of white cheese that I’ll have to seek out at the European Market here in Rocklin. I ate lunches and dinners out with colleagues from the conference and tried French fries with mayonnaise at the encouragement of a Belgian friend. I won’t lie… I kind of liked it.

I saw more of Montenegro on a cultural excursion planned for the morning following the conference. (Yes, the morning after our late-night rager. Thank goodness things were on “Balkan time” aka “15-20 minutes late” and I made it to the bus!) With the sun finally shining we made our way through the hills to the city of Budva on the coast. As we arrived I was pleasantly reminded of Santa Barbara in the coastal plants, animals, weather, and landscape. We dismounted the bus at a dock and boarded a large boat that took us out to the Adriatic Sea, dazzling us with stunning views of the wooded coastline dotted with stone chapels. It was during this voyage that I took about thirty minutes to carefully debone a fish for my lunch and had my first taste of bambus, a traditional and dubious mixture of red wine with Coca-Cola. I didn’t hate it… We landed at a fortress-port-city called Kotor, which is home to literally hundreds of (well cared for) stray cats, as well as the wonderfully winding cobbled streets of an old city that I adore. Here from the sea the mountains shoot up steeply into the cloudy sky (like Santa Barbara), and perched high above the town sits Kotor Fortress, accessible by a marathon of stairs, which, unfortunately, I didn’t have time to explore this trip. By chance I did run into a street vendor playing a sweet Dorian melody on a frula or wooden flute with the fipple hole on the bottom, resulting in a purchase that has augmented my personal woodwind collection.

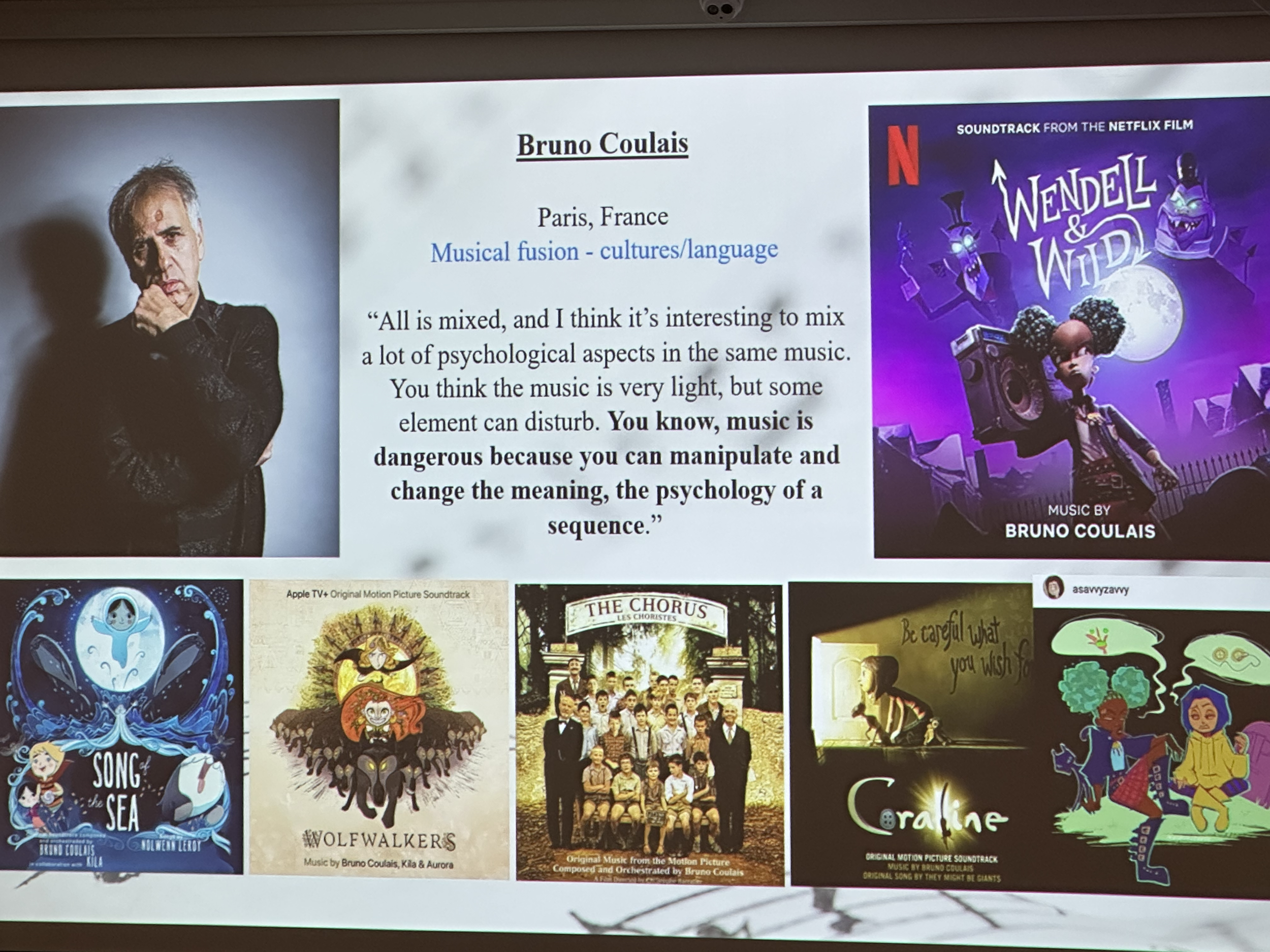

International travel always includes adventures in language and I had some great encounters both en route and in Montenegro. I did some research before the trip and found out that the political and ethnic complexities of the Balkan region is in many ways reflected in the generic boundaries of various languages. Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian are all basically mutually intelligible languages, although to some the symbolic differences are more important than the linguistic similarities. As you might expect, Montenegrin is the official language of Montenegro (but only since 2008), however I found many more resources on Serbian online, so that’s what I worked on. Around town I was able to give greetings, ask for directions, order coffee, and inquire whether I could pay with a credit card. The most fun I had was with Ljubo, the genial man who ran the breakfast at the hotel; we chatted together about Podgorica, food, language learning, the weather, and California. I also talked a bit with two managers of a bookstore (who assured me that “srpski” and “crnagorski” are the same language) where I found a Serbian version of Hari Poter. It turns out that the Serbian word for Muggles is Normalca [normals]. On the trip back to the western hemisphere, I hung out with a Canadian friend from Norway and chatted a bit in German with the scholarly expert on lying and deception, Jörg Meibauer. I also thoroughly enjoyed watching the 2020 animated children’s film “Wolfwalkers” with music by Bruno Coulais on the lengthy flight home.

Wonderful trip! The conference was rich with musical ideas and I truly loved reconnecting with old friends and making new ones. I’d love to go back to the Balkans again some time (Svetlana said to give her a call) and see more of the countryside. Doviđenja! See you next time in Rouen, France!