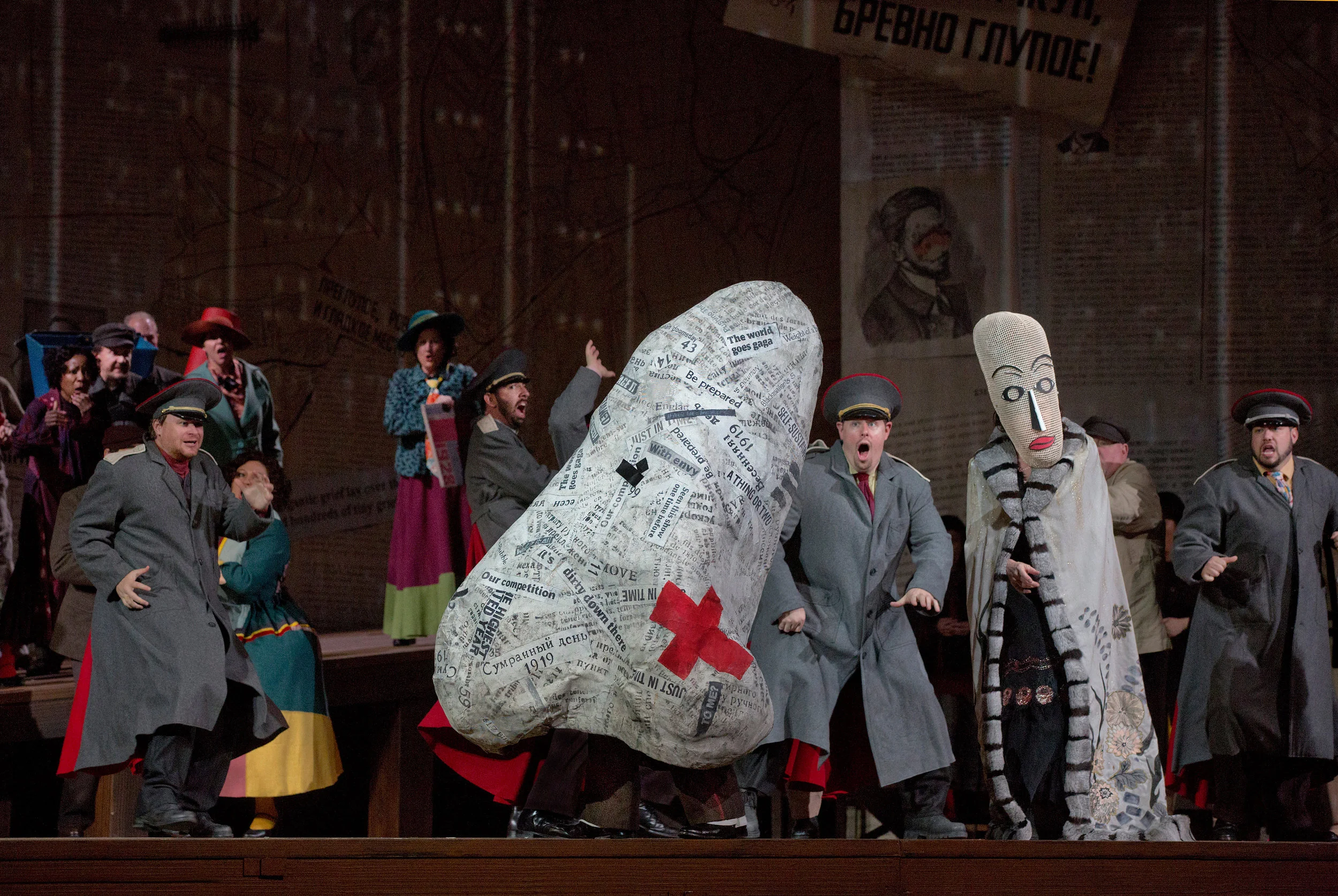

On December 1, 1930 a concert was held at the Glasgow-based Active Society for the Propagation of Contemporary Music. It featured a live performance by Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji, the highly-idiosyncratic and somewhat eccentrically reclusive English pianist-composer, playing his Opus clavicembalisticum, an extremely complex, long-winded, and demanding piece: demanding equally for the performer as for the listeners. Check out John Ogdon's 1988 recording on YouTube for a taste. Here is section five out of twelve. (Note the multiple staves!)

"The Grand Piano #3" by Colette W. Davis. link

Diana Brodie, the wife of the Active Society's president, Erik Chisholm, was present at this unique event and had the following colorful recollections.

"The music, so unlike anything I had ever heard before, was literally terrifying... Floods of notes, cascades of arpeggios, fugal subjects a mile long, yet all conjuring up the most fantastic pictures in my mind. But there was nothing I could understand.

"After about 10 minutes of this, I found myself sitting twisting my fingers in sheer misery, hoping against hope that each crescendo was the final one so that I could get out of the hall for a breath of air. But it went on and on. The whole audience was spellbound. Never have I known such absorbed listening. I really believe that, if the work had continued for 15 hours no one would have dared to leave the hall before the end. Sorabji had his audience mesmerised...

"The second part seemed to be a complete repetition of the first! My musical friends however assured me afterwards that I was quite wrong. 'Well' I said, exasperated, 'I bet there were a lot of other people in the hall who couldn't tell the difference either.'

"By the time the performance had been in progress for two hours and five minutes (never have I looked at my watch so assiduously) even Sorabji was beginning to show signs of war and tear. By now, I was beyond showing any reaction, whatever, except an occasional wistful look at the door, and praying that I would soon be at the other side of it. The old proverb 'It is always darkest before the dawn' was definitely proved to me on that memorable evening. the last 10 minutes were almost unbearable; the perspiration was pouring down Sorabji's face. It was pouring down mine too if he had but known it, only in some mysterious way I seemed to be crying at the same time, filled with a strange sense of fear and frustration. In some ways I think it must have been the same sensation you would expect to feel if a snake had you hypnotised and you were completely unable to break the spell.

"Up and down with tremendous crescendos, down and up with beautiful diminuendos (I did like the diminuendos) each crescendo raising my hopes, each following diminuendo flattening them till at last with one might cataclysmic sweep Sorabji finished playing his first and only performance of 'Opus Clavicembalisticum,' which by the way, in simple language means 'a piece for the piano.'

There was an utter stillness in the hall and then a tremendous applause broke out. Whatever one thought of the music one could not fail to admire the virtuosity of the performance.

"Slowly, so very slowly, Sorabji took out his pocket-handkerchief and wiped his face. Slowly inch by inch he lifted himself out of the piano stool and holding on to the piano lid supported himself to give an enfeebled bow and left the platform to return many times.

"Slowly, so very, very slowly I managed (without the aid of anything) to get out of my chair—I stood up, and at my feet fell a veritable bag of confetti! Unconsciously during the performance I had been tearing my programme into little bits!" (Purser, 64–65)

Sorabji (1892-1988) in 1977. (Sir Jeremy Grayson)

The demands such music places upon listeners easily justify Diana's reaction. Many musical trends that emerge in the twentieth century are equally concerned with complexity and incomprehensibility for a variety of aesthetic, intellectual, expressive, or cultural reasons. A few years ago I had the opportunity to hear a live performance of Schoenberg's Pierrot lunaire (1912) at Eastern Washington University. I took along my wife. She has not forgiven me!

- As performers of twentieth-century musics how should we negotiate this communicative gap with our audience? Pre-concert explanations? Disclaimers? Analyses?

- As teachers of twentieth-century musics what approaches have been most helpful in explaining the music's raison d'être to students?

- Is it worth the trouble? Or should listeners simply be overwhelmed by the unknown and frightening?

Source:

Purser, John. Erik Chisholm, Scottish Modernist (1904–1965): Chasing a Restless Muse. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2009.